She had become obsessed with Scotch. A creative director at an ad agency during the day, she started organizing tastings in her free time to learn more about the whiskey. She blended different Scotches together, blindfolding dozens of people and asking them to tell her which they liked best.

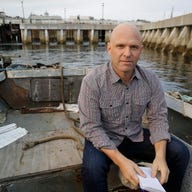

So she decided to craft her own Scotch, even though she lived half a world away from Scotland, the spirit's mandated origin. The obsession has turned into a nascent business: Luna-Ostaseski has raised tens of thousands of dollars on a crowd-funding Web site, connected with suppliers around the globe and begun the hard work of developing a new Scotch called SIA.

She is just one of many new voices in a burgeoning U.S. market for small-batch and craft spirits attempting to innovate how the business is done, not to mention the addition of bold new flavors and cocktails. Over the past decade, the craft industry has gone from a few pioneers like San Francisco's Anchor Distillery to hundreds of small companies scattered throughout the nation. And some distillers aren't simply happy with making delicious classics like bourbon or Scotch. Instead, they are pushing the envelope, making new concoctions that would seem otherworldly to the moonshiners of the past.

"There's no comparison. Ten years ago there was really no national market for legitimately 'craft' whiskey in this country," said Clay Risen, author of "American Whiskey, Bourbon, and Rye." "There were examples of small-production whiskeys (in the past), particularly on the West Coast, but it has only been in the last six or seven years that we've seen rapid growth in the sector. Since then, though, it's been on a rapid growth rate, picking up in the last year especially."

There is a difference between "craft" and "small-batch" manufacturing. Craft spirits are made by small, independent companies; small-batch spirits can be made by large distilleries and the term is often used to describe their high-end, or experimental, products.

Like small-batch beers, the relative freedom that making small amounts of a spirit provides creative distillers is leading to envelope-pushing new drinks: botanicals like fennel- and thyme-infused spirits now can be sitting alongside standards in many urban bars.

While the rise of craft spirits is a national phenomenon, Northern California has a long history of supporting and inspiring spirit-obsessed entrepreneurs like Luna-Ostaseski.

This month, she is launching the simply-named SIA, a Glasgow, Scotland-made blended Scotch whiskey made to her exact flavor specifications. The name is the Gaelic word for the number six, and her hope is that is will become an entry-level Scotch that will inspire people who are wary of the spirit.

"If someone says to me 'Oh, I don't drink Scotch,' it's like them saying, 'I don't drink red wine because I drank it once and it was too strong,'" Luna-Ostaseski said.

Pushing the envelope

In many ways, Northern California is the perfect spot for the first Kickstarter-funded Scotch. It's also been a place where craft whiskeys, ryes and brandies took hold decades before the current trend.

At Anchor Brewing Company's longtime home in San Francisco's Potrero Hill neighborhood, the bitter smell of sourdough yeast hangs over the sidewalk. Inside, behind the heavy wooden doors of the brewery, the sweet smell of wet grains mixed with the piney, marijuana-like scent of hops is startling.

This is a region that likes its beers hoppy -- but would that also work in a spirit?

Anchor is best known for its steam beer, but there is another side to the company that is tucked away, deep in the back of the brewery: past the coverall-clad brewers tending their copper mash tuns and open-top vats of fermenting ales lies a 20-year-old distillery. Here the company's distillers watch over very small batches of rye and other specialty and experimental sprits, all made in shiny copper stills with coiled tubing that looks like giant springs.

Anchor's founder, Fritz Maytag, built the copper pot stills after deciding that Americans hadn't lost their taste for rye whiskey as the market seemed to be saying -- rye was the most popular quaff in the 1800s then disappeared. So Maytag began a clandestine mission to bring the drink back to the people.

"Fritz didn't let people down there to see the distillery," said David King, president of Anchor Distilling Co. "It's much more difficult to distill than brew beer, there are many more steps. And the way you design your stills affects the spirit."

It's no surprise that Northern California is still a center of innovation in the craft distilling business. Its roots here run deep: Hubert Germain-Robin and Ansley Coale started making alembic brandy in remote Ukiah, Calif., in 1982. The company makes just a few hundred cases of its prized brandy each year, recognized as some of the finest in the world, with each bottle retailing for $350.

"(Maytag) was certainly ahead of his time and was doing things 20 years ago -- moving from beer to whiskey, working with rye, exploring traditional styles and production methods -- that are only now getting popular," Risen said.

Hopheads

Maytag in 2010 sold Anchor to alcohol industry veterans Keith Greggor and Tony Foglio, who helped develop Skyy Vodka. The pair later took over Preiss Imports, which deals in specially-made spirits.

The company's president, David King, has a background in developing flavors in all sorts of commercial food and beverage products. One day he was walking by bales of fresh hops in the brewery hop room when a light bulb went on.

Beverage marketers consider vodka a drink that appeals to women more than men, but King thought hops could be used to change that.

So the distillers began experimenting with grain-neutral alcohol, and after a number of failed attempts, they concocted a small-batch spirit that for the first time features the cannabis-like plants used to flavor beer: hops.

"The first version wasn't pretty, so we started asking why," King remembered. "It took us six months to get it right."

The result is Hophead Vodka, which uses a proprietary blend of both bittering and aroma hops (bittering hops are higher in alpha acids and are usually used in adding bitter flavors to beers, where aroma hops are less acidy and add nose to a beverage).

In a hop-obsessed market like Northern California, bartenders have already found takers in Hophead vodka gimlets and Bloody Marys.

The drink is innovative in many ways, but especially because it's called a vodka. Vodkas are usually defined by regulators as a spirit with no definable flavor or character, and the bitterness and flowery nose of the Hophead is full of both.

King hopes anyone who doubted Anchor's future as an innovator after Maytag sold the company will look at Hophead as proof that the company is still on the cutting edge.

"Part of the Anchor Distilling Co. legacy that Fritz started was always doing stuff first," King said, "and I'm hoping we can continue that."

Old meets new

Luna-Ostaseski shares photographs of the first delivery of her 150 cases of SIA Scotch like a proud new mother. Each case has six bottles -- she's starting small, with two San Francisco stores on board and a distributor following soon so she can learn from early mistakes without them costing too much.

So far, SIA has gotten more attention for its innovative origins than its flavor, but even Scotch experts have given some positive critiques. Ian Buxton, a Scotch expert, told the Scotsman newspaper: "(SIA is) fresh and malty, with a bit of banana and fruit cake" and "well balanced with just the right amount of smokiness combined with a pear drop sweetness."

Luna-Ostaseski knows she faces an uphill battle. With a business based on centuries of tradition, the world of Scotch hasn't been the easiest to penetrate for a woman from San Francisco.

"You've got these older people making an older drink that's aged forever and is very cherished," Luna-Ostaseski said. "But it's almost like an old boy's club, like you're going to this country club and they won't let you in."

"I see SIA as a gateway," she said, "so if I introduce people to other kinds of Scotch then I've done my job."

Photo: SIA Scotch

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com